|

We’ve talked about ‘green’ pesticides before. Many ‘green’ pesticides contain one or more essential oils in their formulas. Although a number of studies report on the supposed efficacy of essential oils against insects, we see, comparatively, relatively few essential oil pesticide products on the shelf. Why? In this week’s blog, we’ll go over some of the pitfalls related to essential oil product development that have more to do with product development and less with political, legal, and personal stances on the ‘green’ pest management movement. However, for a commentary on those topics—check out our other blog post linked above! Times Are ChangingRegardless of whether you agree with the practice, there is a very clear and increasing demand for products that consumers consider to be “natural”—especially when it comes to pesticides. A quick Google search for “natural pesticides” turns up more pages of results than we have time to navigate, as well as a number of blog posts (some from governmental entities) with DIY recipes for “alternative insecticides” that are, in theory, less harmful to the environment. Most of these recipes call for the use of essential oils. According to the National Institute of Environmental and Health Sciences, essential oils are “concentrated plant extracts that retain the natural smell and flavor of their source.” The use of natural products to control pests is not a new concept. Chrysanthemum flowers, which contain pyrethrins (an insect nerve toxin), were identified as insect-killers as early as 400 B.C. Their use is not outdated, either--we still use pyrethrins to control a number of urban pests. But, if you look at the history of pest management, there was a definite, clear shift toward the use of synthetic pesticides once they were developed. With increased use came increased scrutiny, however, and a number of negative environmental consequences related to synthetic insecticide use have been identified over time. Recent environmental movements have spurred the pendulum to swing back toward more natural compounds to protect pollinators, the soil, air and water quality, as well as human health. Limited 'Natural' Product AvailabilityEssential oils and other related natural products are considered attractive alternatives to synthetic chemicals for insect pest management. The efficacy of many of these compounds has been demonstrated in peer-reviewed scientific studies. For example, mint oil can be repellent to fire ant workers and neem oil can kill bed bugs. But in spite of preliminary laboratory trial successes, there simply aren’t all that many EO products on the market. Why? Authors of a recent study have identified a few issues with EO compounds that could be the limiting factors impacting commercialization of EO insecticides. First, EOs tend to have high volatility, meaning they evaporate pretty quickly. This allows EO compounds to serve as great fumigants, but, if a compound evaporates too quicky, it can impact efficacy. Evaporation of product means that there is no residual deposit left to kill insects that visit treated sites later. This is one of the main benefits of many synthetic products. If you have to re-apply EO products over and over to achieve the same result as a synthetic counterpart, labor and other tradeoffs may be unattractive to consumers or pesticide applicators. Additionally, we still don’t completely understand how many of these EO compounds act against insects physiologically. Without understanding how these compounds work, it is difficult to start developing products that kill bugs in a consistent way. This may deter end users who want to know exactly how a product will perform in a given situation. For example, we know exactly where pyrethroid compounds act on insects and can explain their function clearly to end users. From product to product, they perform fairly similarly. We know how to rotate products when pyrethroid resistance to this synthetic active develops. EOs are much less predictable. Finally, sourcing EOs can be exceptionally problematic. The cost of any given EO varies immensely depending on how oils are extracted and distilled from plants. Marketing can also be confusing. For instance, makers of “lemon eucalyptus oil” hint that this compound is the same as “oil of lemon eucalyptus”—but they certainly are not equivalent. Lemon eucalyptus oil is cheaper to produce and does not have the same mosquito repellent properties. These sort of mix ups make the EO product landscape confusing for consumers and difficult for manufacturers. Without organizational oversight and regulation, it is difficult for manufacturers to justify the high cost of production for quality oils when consumers often opt to purchase lesser quality product at a lower cost. Currently, many EO products are exempt from FIFRA registration. Although this makes the registration process much faster and lower cost, it also means less oversight and an uneven competitive landscape. Until the registration model changes, including the adoption of more stringent efficacy testing requirements for EO products, we may continue to see a lack of innovation in this category from many pesticide manufacturers.  The published efficacy of some EO insecticidal products, like citronella candles, varies; yet, citronella candles are still sold for this purpose. More oversight in the EO pesticide market might lead to a more level playing field for manufacturers, and ultimately, more efficacious products. (Image Credit: Vilseskogen, Image Source: Flickr) ConclusionsEO products have potential to serve as novel, innovative compounds that can be used effectively in pest control. The efficacy of many of these compounds has been confirmed in laboratory trials. Yet, adoption of EO products by the pest management industry and widespread availability of effective natural compounds for consumer-based pest management is currently lacking. It would be wonderful if we had access to additional active ingredients to combat pest infestations. Hopefully, the issues highlighted here are addressed to allow for more proliferation of effective natural EO compounds that are equivalent (or close to equivalent) to their synthetic counterparts in the marketplace. This would allow manufacturers to meet the clear consumer demand for natural product alternatives, as well as the product effectiveness needed by pest management professionals whose livelihood depends on delivery of functional insecticides.

0 Comments

Many in-home pest problems can be solved or significantly reduced with pest-proofing through exclusion. If a bug can’t get inside, it can’t cause a problem, right? In this week’s blog, let’s discuss a few ways to make your home impenetrable to the army of insects and other pests trying to find their way inside before insects start to set up shop indoors during the fall. How to Pest-ProofDid you know that a house mouse can enter a dwelling through an opening as small as ¼” in width? Small and often overlooked openings in and around the home provide a perfect way for pests to invade your space. Pest-proofing is important because not only can it prevent pest entry, it can reduce pest movement and establishment within a structure, too—making bugs and other pests easier to control if they do somehow get inside. Termed “exclusion”, this step is often one of the first in an integrated pest management plan. Exclusion is an effective way to control pests without the need for pesticides. Many of the materials you need for pest-proofing are found at your local hardware store and are probably materials you have used before for simple home repairs (note: this may not be the case for rodents—see this article for help with proper rodent exclusion). Otherwise, here a few easy things you can do to take the steps required to block entry before pests give you a headache. 1. Apply caulk to the cracks around windows, doors, and other exterior-facing components of the home. To see where there are points of entry, turn on the interior lights and walk the exterior at night. Use silicone or acrylic latex caulk to fill any areas where light escapes. Acrylic latex is less flexible than silicone, but cleans up easily with water and it can be painted over. If the area is likely to take on water frequently (e.g., under sinks, around bathtubs or toilets)—use silicone. If you are worried about aesthetics, clear-drying caulks are easier to use because they do not show mistakes like pigmented caulk. 2. Apply silicone caulk to tubs, toilets, pipes, and any other area where water tends to pool and/or leak. This will discourage the entry of insects looking for water. 3. Seal any utility openings that are present. These sites are where pipes and wires enter the foundation and siding, such as around outdoor faucets, gas meters, dryer vents, etc. These are exceptionally common entry points for insects and other animals. You can close these openings with a number of materials—really any suitable sealant is appropriate. The choice will depend on the site, as well as how large the opening is. Example materials include, but are not limited to, cement, caulk, expandable foam, and steel wool. 4. Install door sweeps and weather stripping on and around all doors. Like we mentioned in step one, you can assess whether there are gaps around door frames by looking for light filtering in above, below, and around the sides of the doorway. Gaps of only 1/16” or less can allow insects and other arthropods inside. Keep in mind that corners are the most susceptible to pest entry. These recommendations apply to garage and sliding doors as well—in general, garages are also especially susceptible to pest entry. 5. Make sure that all window and door screens are in good repair. This will cut down on the entry of flying insects. However, very small insects like leafhoppers or gnats are able to penetrate standard-sized window screen mesh. If you see high numbers of small insects and you have evaluated your screen for holes or tears and found none, the best solution is to leave windows closed during periods of high insect activity. If you really would like leave the windows open, sticky traps/fly paper can quickly capture flying insects as they enter.  Window screens and gaps around windows are a forgotten way that insects gain entry into the home. Ensure that all tears and rips are repaired, especially since insects that are attracted to light will often fly to windows when it starts to get dark outside. (Image Credit: Darrin Henein, Image Source: Unsplash) 6. Wire mesh can be installed over vents in the attic, roof, or crawl space. Chimney caps exclude nuisance vertebrates like birds and racoons. The mesh used in these areas should be ¼”. Be careful during installation as the wire can be quite sharp at the edges. 7. Deal with standing water and other areas that hold moisture. Trim back bushes so that they offer less shade to insects. Make sure that ornamental plants are not touching the structure, as this essentially gives insects a bridge right into the home. Be sure to fill or otherwise eliminate holes in the yard that hold standing water, even for a short time. 8. Take this time to do a pantry clean-out as well. No tools required! Throw away expired foods, store foods in in glass or plastic instead of cardboard or paper, and make sure that none of your food products have any evidence of insect or rodent activity (e.g., frass, webbing, gnaw marks). ConclusionsDon't wait until fall when it is too late and pests have already made preparations for invasion. Instead, be proactive! These small improvements to your home will help with resale value, they can stabilize energy costs, and, importantly, keep pesky critters outside, where they belong. Last month on the Bug Lessons blog, we took a deeper dive into the specific components of IPM. This month in our IPM series, we’re taking a closer look at the pest identification process and action guideline setting for your program. These introductory steps are crucial in designing an effective pest management program—read on to make sure you’re executing these critical steps correctly! Pest IdentificationIf you recall, in our first couple of blogs, we emphasized that it is critical to properly identify the pest in question before engaging in any sort of pest management strategy. Treating for the wrong pest can cause failure of an IPM program because a successful program hinges on understanding pest biology and behavior. Here are some helpful tips and resources that will have you feeling like an entomologist in no time!

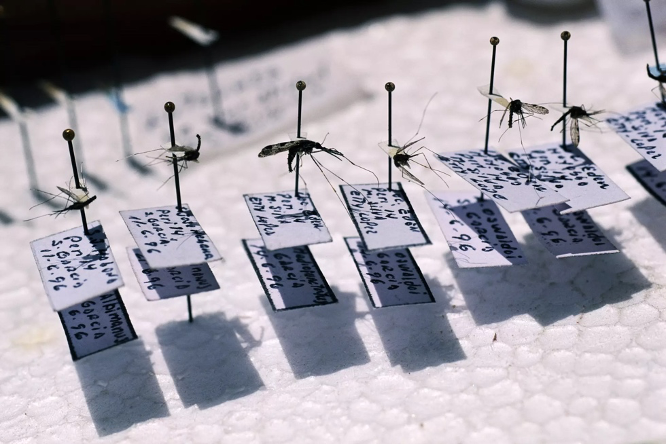

We’re borrowing this from our first IPM blog because it’s important! Getting the correct insect identification is crucial for effective pest management. Diagnostic entomologists and taxonomists specialize in the identification and classification of insects. If you need assistance identifying a specimen, contact an extension entomologist or utilize the online bug guides we referenced in this blog! (Image Credit: Chris Martin, Image Source: Getty Images) Once you have all of this information, there are a few ways to proceed. If you think you can identify the insect yourself but need a little help/confirmation—there are some great online databases that can help. For instance, BugFinder allows users to start an ID based on the silhouette of the pest in question. Another helpful website is BugGuide.net, which even has an option for registered users to make identification requests. Community members on the website are often more than happy to chime in with assistance! If you prefer to have someone else make the identification for you, reach out to an extension specialist and entomologist employed at a land-grant university. The USDA has a handy list to help you find the university closest to you. Department webpages often list the extension faculty for the public to access. You can also reach out to cooperative extension offices, where an extension agent might be able to assist. Please remember that entomologists are NOT trained medical doctors or dermatologists. Rashes/bites/tissue samples, etc., are not the way entomologists identify insects and they will not make pest identifications based on suspected bite reactions. If you suspect you are dealing with a pest that is causing bite marks, allergic reactions, and other maladies and you cannot obtain a physical sample of the pest, seek help from a medical doctor before consulting entomologists.  When you find a potential pest, record everything you can remember about where and when you found it. What does it look like? What was it doing? What kind of antennae did it have—beaded, like this bug here? Or were they fluffy in appearance? Elbowed, straight? The more details you have, the better a diagnostician can assist you. (Image Credit: Nicolas Brulois, Image Source: Unsplash) Setting Guidelines For ActionOnce you understand what pest is present, how many you can tolerate should be the next question to address. This number will often hinge on a number of factors, such as cost of treatment, environment where pests are present, personal preferences, potential damage the pest can cause—to name a few. However, establishment of an “end goal” so to speak will prevent potentially unnecessary labor and pesticide applications. The ‘action threshold’ is the point at which pest populations are a level that require intervention. It is a difficult metric to assess. It is certainly more subjective than identifying a pest. In urban pest management, specifically, the action threshold is often set from scratch on a case-by-case basis. For instance, one individual may have a much higher tolerance for the presence of wolf spiders versus another individual. When the pest poses a public health threat, like bed bugs or German cockroaches, the threshold required for action is probably as low as the presence of one bug. The action threshold can be set by the individual who is affected, and is a personal choice. If you are having trouble discerning whether or not you should take action against a pest, you can reach out to extension folks with this question, too! ConclusionsIntegrated pest management is a very effective way to manage pests, but the process can seem daunting. We hope that by breaking it down piece by piece in this series makes it more straightforward! It is important to remember that your first IPM plan may not go…to plan! Make sure to give yourself flexibility. For instance, maybe you initially think the presence of five ants is no big deal, so you take no action. However, the next day, 30 more workers show up on your counter and your action threshold changes- perhaps five ants would have been a more appropriate action threshold after all. That’s okay! However, if you need more help with these steps of your IPM plan, feel free to contact us at Bug Lessons, or, contact your local extension specialist. We’re all pretty aware of pesky beetles feeding on our garden plants, or caterpillars chomping down on farmer’s crops. Usually, humans get pretty annoyed when bugs feed on their food. But recently, scientists were able to use insect feeding to help them trace the evolution of plant ‘sleeping’ movements. Did you know that plants slept? Did you know that we could use insect clues to learn more about the evolution of that phenomenon? We didn’t either! Read on to find out more about a pretty unusual approach scientists took to solve a nagging prehistoric plant puzzle. Plants Need Naps, Too!Plants can move in some surprising ways. They move in response to environmental triggers, such as wind, light, gravity, humidity, or contact. In addition, some plants follow a circadian rhythm (repeated every 24 hours) that dictates ‘sleeping’-type movements called nyctinasty. Scientists have been interested in nyctinasty, or plant ‘sleeping behavior’, for quite some time. Charles Darwin was so interested in plant movement; he wrote an entire book about it. Although in this seminal work he clearly noted that plants folded their leaves when they went to “sleep”, scientists continued to wonder, “When did this behavior evolve, and why?” Interesting questions, but as an avid reader of an insect blog, you’re probably wondering what questions about plant naps (Bug Lessons’ new moniker for “cat naps”) have to do with bugs. Well, in a recent study, scientists admitted that they used a pretty unorthodox method to investigate the history of plant sleeping behavior. Wouldn’t you know, it involves our favorite six-legged creatures. For Once, Insect Damage Proves UsefulThanks to Darwin, scientists knew that legumes had more ‘sleepy’ species than all other plant families combined. He also identified the organ that controlled sleep movements in plants. However, questions still remained regarding the origin, history, evolution, and benefit of sleep movements because there was no fossil evidence for this process the fossil record. It was impossible to tell if fossilized plants were actually sleeping, or, if they simply died and shriveled up prior to becoming fossilized. Recently, though, scientists documented sleeping behavior in fossilized plants by looking at insect feeding damage on the fossilized leaves from the upper Permian of China. Based on the age of the fossils, scientists could conclude that plants were taking naps as long ago as the late Paleozoic era (250 MYA). Other notable events that occurred in the Paleozoic era included the formation of Pangea and the Appalachian Mountains.  Plant fossils are typically incomplete and they are of course static. This makes it difficult to understand what exactly happened during the period of fossilization. That is, without having more information (such as details re: plant-feeding damage). (Image Credit: James St. John, Image Source: Flickr) The lead author of the research study, Dr. Feng, was able to figure out that prehistoric insects fed on sleeping leaves based on correlations with insect-damaged leaves he collected in 2013. In the modern (2013) plant samples, Feng noted that insects cut symmetrical holes in leaves because they were feeding on samples when plants were asleep, i.e., when the leaves were folded. Dr. Feng saw identical symmetrical holes in the fossilized leaves. After combing through hundreds of fossil samples, Dr. Feng and his colleagues were able to conclude that i) plant sleeping behavior definitely occurred prehistorically, ii) plant sleeping evolved independently in lots of different plant groups and iii) the pervasiveness of the behavior indicates that it serves some benefit for plants. The study is innovative not just because authors used insects in a unique way, but also because the findings prove that we can identify organismal behaviors, not just structures, in the fossil record. This opens up fossil samples to all sorts of new investigations that were previously untapped. And all because insects are continuing to do what they’ve always done—eat a lot of plants! ConclusionsObviously, fossils are not very dynamic. It is difficult to tell what was happening at the time of fossilization for many organisms. However, we know that insects have been around for millions of years, and they interacted with many different organisms. It will be interesting to see what else we will glean from other fossils based on how insects interacted with them. Hopefully, this gives the masses as well as other scientists a deep appreciation for the sometimes very unexpected roles that insects can play in terms of scientific discovery. |

Bug Lessons BlogWelcome science communicators and bug nerds!

Interested in being a guest blogger?

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|