|

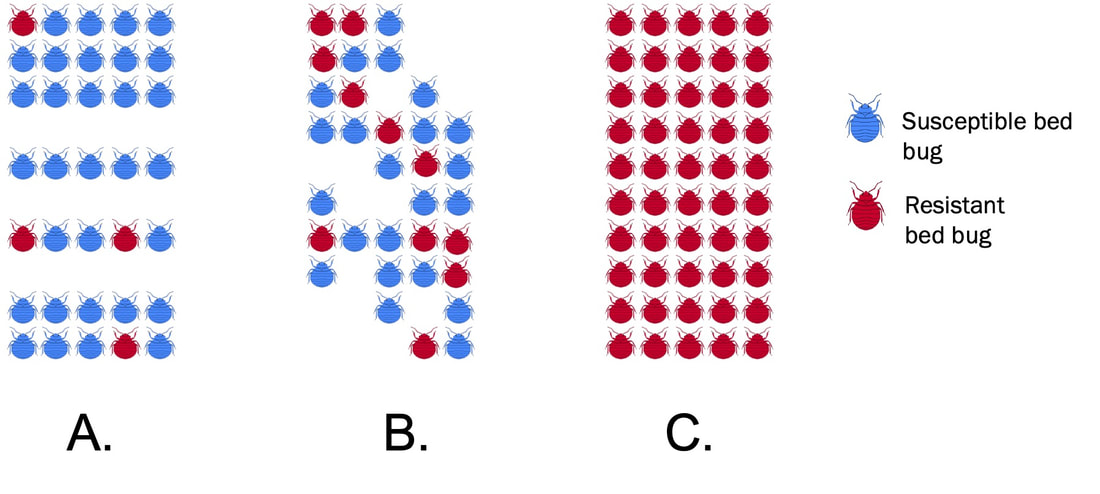

Insecticide resistance can result in product failures and pest infestations getting out of control. Does that mean all hope is lost? How can people stop insecticide resistance from happening? This week’s blog provides a little knowledge about the traits that allow insects to survive exposure to an insecticide and ways we can prevent this phenomenon from occurring. Scientists group insecticides into classes based on different commonalities they share, such as the way they kill bugs (e.g., their mode of action). For example, the class of insecticides called organophosphates (OPs) all work by interfering with an enzyme involved in nerve function. By interfering with this enzyme, normal nerve signals fail, the insect’s behavior changes, and ultimately, the insect dies. The enzyme affected by the OP is called the target site. The target site is the exact place where the pesticide exerts its killing action. How is all of this related to insecticide resistance, though? When people repeatedly use products with the same mode of action, resistance can develop. In groups of bugs, a variety of individuals exist with unique physical and behavioral characteristics—and some of them may have genetically based traits that make them less likely to die from pesticide exposure. Using a pesticide kills the majority of individuals in the population. With enough time, the repeated use of the same or similar pesticides kills the susceptible members of the population until only the individuals that can survive exposure remain. WHAT KIND OF TRAITS ALLOW AN INSECT TO SURVIVE EXPSOURE TO AN INSECTICIDE? Scientists have identified relatively few ways that insects use to survive exposure to an insecticide.

Another strategy uses a product that has two different modes of action (combination product), or a tank-mix. By using multiple modes of action at once, hopefully there will not be individuals in the population with the right mechanism(s) of resistance to overcome simultaneous killing methods. However, over long periods of time, this method may still select for insecticide resistance. For more information on tank mixing, visit the Pesticide Environmental Stewardship website. Maintaining susceptible individuals with susceptible genes that can interbreed with resistant individuals may also delay resistance. In agriculture, pest managers may do this by not spraying dedicated areas within or near fields to create safe spaces or refuges for susceptible insects. However, in some environments like people’s homes, allowing any insects to persist may not be acceptable. FINAL THOUGHTS Evolution is a process that allows animals to survive, even in changing environments. Thus, we should not be surprised that insects can adapt to environments where insecticides are applied. As of now, over 500 species of insects demonstrate some form of insecticide resistance. Once a population has become resistant, professionals have a challenge lessening that resistance. Reversal of resistance can occur by allowing extensive time between applications of insecticides. However, this is not always reasonable, and no one can know if a resistant population will revert back to the same level of susceptibility. The best way to stop resistance is preventing resistance. With a little bit of knowledge, everyone from consumers to professionals can help delay the selection of resistance.

0 Comments

Scientists talk about the importance of insecticide resistance often, but what is insecticide resistance? How can insecticide resistance be prevented? This week’s blog discusses some insecticide resistance 101, different ways insects survive insecticide exposure, and why you need to know. Bug Lessons regularly advocates for the importance of integrated pest management (IPM) and science-based pest control to effectively manage or eliminate pest problems. Using multiple tools and data-driven treatment decisions to manage pests can reduce chemical insecticide use, which results in fewer environmental contaminates and prolongs the effectiveness of insecticide products. But how? Sometimes when a person uses the same product or active ingredient repeatedly, insecticide resistance can develop. Insecticide resistance is a change in how sensitive insect populations are to a particular insecticide and may result in failure of the product to control the insects. In other words, the insecticide once killed the bugs, but now they walk right through the spray like a gentle rain in May. HOW DO PESTICIDE APPLICATIONS RESULT IN INSECTICIDE RESISTANCE? Certain environments favor the survival of individuals with certain physical and behavioral traits. When a person uses an insecticide to kill insects, some insects may survive exposure because they are naturally different from the majority of the members in their population. These survivors are the ones who reproduce and, ultimately, spread the genes that made them different to new members of the population.

WHAT CAN I DO TO HELP? Insecticides are critical for protecting our food supply, reducing disease transmission, and protecting human and animal health. To preserve these useful tools, carefully consider how and how much insecticides you apply. Science-based pest control or IPM is a multi-step process utilizing all tools available and reasonable and uses data to inform treatment decisions. First, try to monitor pest populations and assess the level of damage before deciding whether the application of an insecticide is necessary. The presence of a pest does not always necessitate action or treatment. However, if treatment is necessary, decide whether other control measures can be employed, such as biological controls (predators/parasites), mechanical control, or sanitation. When applying insecticides, alternate between different insecticide classes if multiple applications are necessary. When choosing different insecticides to include in your program, consider the following:

If you think that you might be dealing with a resistant population of insects, report the problem as soon as possible to a local extension specialist at a nearby university. These folks should be able to help assess whether resistance is present, and if so, what type and what to do. Note that in some cases you might be dealing with ‘tolerant’ versus ‘resistant’ pests. Tolerance is not the same as resistance. Tolerance is a natural tendency and is not related to a tangible, genetic change in the population. For instance, you may see a difference in efficacy of a pesticide against different life stages of a pest. Older life stages of an insect may be more tolerant of insecticide application than younger life stages due to morphological characteristics such as cuticle thickness. Again, an extension specialist can help you tease apart any chemical failures you observe and assess the situation for you if you are unsure. FINAL THOUGHTS Insects and other animals can adapt to changing environments—that is why there is so much diversity in the world. However, their ability to rapidly adapt to change also allows insects to survive exposure to insecticides and become resistant, sometimes within a few generations. The best way to stop resistance is to prevent resistance. Using insecticides thoughtfully and sparingly can help prevent resistance by keeping susceptible members in the environment. For more information and resources on using pesticides more effectively, visit the Pesticide Environmental Stewardship website. Have you ever chosen a product because marketing materials contained words such as “safe” or “organic”? Do these words mean a product is better for the environment or human health? Sometimes the technical definition of the word does not completely match with the perception. In this week’s blog, let’s discuss the meaning of sometimes misunderstood terms like “safe” and “organic”, and how they relate (or don’t) to the toxicity of a pesticide. The recent media spotlight on glyphosate has ignited renewed conversation on pesticide safety. Bayer (which acquired Monsanto) continues to address legal action around the claim that the active ingredient (glyphosate) in the popular herbicide Roundup™ causes cancer. The claim and resulting media frenzy has caused discord in both the scientific and political communities. This is understandable, given that evidence for glyphosate’s carcinogenic properties exist, but the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has concluded that glyphosate poses “no risks of concern to human health” when used as directed. Media coverage on pesticides can make people anxious, which may be one reason why consumer research shows that people are seeking alternative, “green” solutions. However, terms like “safe”, “organic”, and “all natural” can make a product seem less hazardous to either the user, the environment, or both. That may not always be the case. According to the University of Illinois Extension, “…like synthetic pesticides, organic products have a broad range of toxicity levels.” The article goes on to say that botanical insecticides (pesticides made from plants) can be more dangerous to the environment than synthetic counterparts. REGISTRATION AND PRODUCT LABELSThe Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) is a written law that governs how pesticide products are registered, distributed, sold, and used in the U.S. This law requires pesticide products to be registered with the EPA (although there are exceptions to this). Before EPA will register a product, the applicant must submit studies to prove that the product does not cause “any unreasonable risk to man or the environment.” To do this, the applicant must show what will happen to humans if the product is eaten, inhaled, or comes in contact with skin and what impact it may have on the environment. EPA also requires most pesticide products contain a signal word that ranks the relative acute toxicity, or the ability of the product to cause injury or illness. The signal word on the product label reflects the results from the test with the highest acute toxicity. DANGER reflects a high toxicity, WARNING is moderately toxic, and CAUTION is the least toxic. These signal words will impact the personal protective equipment (PPE) and other language required on a pesticide label. A lot of danger can be mitigated when exposure to a chemical is limited, such as through the use of appropriate PPE during application. As the toxicity of the product increases, the required PPE increases as well. This is why all Directions For Use emphasize using a product according to the label. Labels contain valuable information designed to protect people and the environment. SAFE, ORGANIC, AND GREEN

“Even though these products [Minimum Risk Pesticides] may not require federal registration, most states will require the product to be registered in their state before it can be sold,” said Dr. Janet Kintz-Early, urban entomologist and registration expert with JAK Consulting Services. “States may allow the word ‘safe' as a marketing claim if followed by the phrase ‘when used as directed’.” Dr. Kintz-Early went on to say that small and start-up businesses may not realize that they are selling a pesticidal product or that their state and/or the federal EPA may require their product be registered. “There are many products for sale on popular e-commerce sites that claim they are ‘safe’ or ‘non-toxic’. These products could literally contain anything,” said Dr. Kintz-Early. “Nothing is safe if you are reckless. All products should be used only as described in the Directions For Use and with an abundance of caution.” Another tricky term is “organic”. Organic pesticides are generally those that come from a natural source. However, nature can produce some very risky substances, such as snake venom, nicotine, and even peppermint. So, while organic active ingredients are naturally derived, they are still pesticides meant to kill pests. Furthermore, the word organic on food is a very specific term defined by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). According to the USDA, “Organic is a labeling term that indicates that the food or other agricultural product has been produced according to the USDA organic standards.” Organic, in terms of food production, does NOT mean that no pesticides were used to produce the food. Perhaps the trickiest word of all is “green”. Currently, the term is not defined by any regulatory agency. As a result, different consumers and marketers can interpret the word differently. Additionally, just because a product contains words such as “natural” or “green” does not mean the product contains no risk. RECENT RESEARCH

FINAL THOUGHTSPesticides allow farmers to grow more food, kill mosquitoes that can spread diseases to people and animals, disinfect surfaces of harmful pathogens in hospitals, and help us conserve food by eliminating pests that eat stored products such as grain (to name just a few). However, whether the pesticide is “green” or synthetic, the best control programs use them as one component of an integrated plan that makes data-driven decisions and utilizes all tools available and reasonable. Undoubtedly, ways to reduce reliance on pesticides as well as the negative environmental impacts they can sometimes have should be explored. However, a “green” pesticide is not always likely to reduce environmental impact simply because the label contains words such as “safe” or “organic”. For more information on what different words mean or help identifying a “lower-risk” pesticide, please visit the National Pesticide Information Center’s Common Pesticide Questions section. |

Bug Lessons BlogWelcome science communicators and bug nerds!

Interested in being a guest blogger?

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|