|

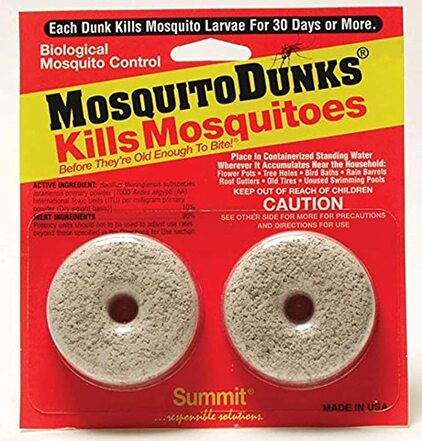

Last month on the Bug Lessons blog, we took a close look at pest prevention. This month in our IPM series, we’re zooming in on actionable items that can be taken to control an existing pest infestation. Although we’re certainly going to discuss the application of pesticides, we’ll also talk about some other things that can be done to effectively manage pests in urban settings. IntroductionWe have mentioned a number of times that creating an integrated pest management (IPM) program requires an elaborate series of decision-making steps. We discussed using a variety of complementary or synergistic tactics to suppress or prevent arthropod pests. Once you have identified the target pest, monitored pest activity, decided on an action threshold, and taken steps to prevent a future pest problem—it is time to start taking steps to solve the issue through action (if a problem still exists after preventative measures). Actionable measures can include both chemical and non-chemical tactics to eliminate pests. These specific strategies will comprise the focus of our monthly IPM blog today! Types of Control and Actionable StepsMost people break up the types of pest control used in an IPM plan into five groups, these include:

At this stage in the IPM program, you can use any tactic from one of the five strategies previously listed to gain control of an infestation. The strategies you decide to employ will depend on the budget available, the environment, the pest species in question, your (or the client’s) tolerance for pest presence/pesticide use, and an array of other factors, too. We of course do not have time in this short blog entry to discuss every single pest control tactic for every single pest and system, but we will provide some examples below. For any specific questions, feel free to reach out to us at [email protected]! Examples of Actions You Can Take Against PestsCultural Control

Mechanical Control

Choose the formulation that will do the job adequately with the least environmental impact. Target-specific baits are a great choice if you want to reduce non-target effects. For outdoor applications, try to choose formulas that are less likely to drift or remain in the soil for long periods of time. Use the lowest label rate that allows you to gain control. Rotate active ingredients if you are using a pesticide for a lengthy period of time, or over and over again (i.e., every season, every two weeks, etc.). Many extension websites have helpful tips for pesticide selection.  Baits are a great way to control an array of indoor pests, especially cockroaches and ants. They are usually pest-specific, and are often contained in sachets or stations that confine the bait to one area. Be sure to read labels carefully so that you apply correctly—baits do not work the same as contact liquid pesticides. (Image Credit: Forest and Kim Starr, Image Source: Flickr) Behavioral Control

ConclusionsIt might take a bit more effort to apply >1 strategy to a pest problem, but IPM programs reduce pesticide risk and are often more effective than management plans that rely solely on chemical use. We could all benefit from a healthier environment, especially indoors and around structures where we spend lots of our time. It may be tempting to buy that ‘miracle product’, but we encourage you to think twice—sometimes when things sound too good to be true, they are. This is especially true in urban pest management.

0 Comments

Last month on the Bug Lessons blog, we talked about monitoring pest problems and assessing damage. At this point, we’ve reviewed roughly half of the steps of a successful IPM program! Before we get into the different types of actions that can be taken to reactively deal with pests, let’s talk a bit about proactive action. Once you know what your pest is, how many you will tolerate, and how to keep track of them, it is a good time to start thinking about ways to prevent the problem from continuing or happening again. So today, we’re going to focus on what to do to prevent callbacks and future pest problems while enacting a pest management plan. Quick Refresher!If you think all the way back to our first IPM series blog, you might remember we mentioned that many pest problems are more effectively solved with preventative versus reactive strategies. To reiterate: sanitation, pest-proofing, reducing hospitable pest environments, etc. should be considered when designing your IPM plan—this way, pests do not return after you have finished your reactive treatments (such as applying pesticides). Prevention should really be the first tool in pest management, because it is usually environmentally-friendly, low cost, and effective. So, let’s talk about a few ways we can keep pests out, while acknowledging that each of the solutions below may or may not be appropriate for each and every situation. For any specific questions or general assistance- feel free to reach out to Jennifer! SanitationKeeping things tidy goes a long way in preventing pests. The fewer things for pests to feed on/hide in/breed on/drink from, the better. There are a multitude of things you can do to eliminate pest breeding and aggregation sites through sanitation. What you choose to do depend on the structure and pest in question, but here are a few things to try (many are situation-dependent):

Proper waste management is critical in controlling pest insects. Pests enjoy the same foods that we do, and often take shelter in our waste items. Sealing these in bags and placing them into bins for regular pickup, as well as storing bins far away from structures, can prevent pest infestations inside structures. (Image Credit: SS Young, Image Source: Wikimedia Commons) ExclusionMuch like sanitation, exclusion is meant to keep pests from accessing potentially attractive items within the structure—i.e., things that they like to feed on, breed/harbor in, or drink from. There are a few steps that can be taken to exclude pests from a structure. These are often done by the owner/occupier of the structure, versus a pest management professional (but not always). Some things to try include:

Remember—mice and rodents can enter through cracks as small as ¼”. Insect pests can get into even smaller places. Don’t underestimate them! For more information--check out our blog on exclusion, here! There are other things you can do to prevent pests, too, that should have been identified through monitoring and inspection. For instance, did you happen to learn where pests were coming in? Through recordkeeping, perhaps you identified a certain supplier that is delivering infested product? Shipments could be discontinued until the problem is solved. Maybe a door is left open too long during the workday and critters are wandering in? An air curtain may be appropriate in that case. For structures where pests are probably going to be a problem no matter what (e.g., poultry farm, commercial kitchen) light or other types of insect traps might be helpful. Whatever you decide, it should (ideally) be something that helps prevent the need for consistent reactive treatments, especially those that involve pesticide application. Although we’ve discussed visual inspections in other sections- they are relevant here too. Regular inspections can help identify new conducive conditions that would encourage pest infestation. ConclusionsAs we’ve stated many times, integrated pest management is a great way to control pests while being conscious about environmental impact and preserving the efficacy of chemical pesticides. Preventing the establishment of pests is an important step in the process. If no pests are present- no treatment is needed! That’s the ideal scenario, right? For more IPM tips and tricks, keep an eye out for next month’s blog where we will finally go over reactive pest management strategies, including the application of pesticides. Over the last couple of months on the Bug Lessons blog, we have taken a closer look at the specific components of IPM. We’ve gone over pest identification and setting guidelines to determine when to use what action. This month in our IPM series, we’re going to discuss the monitoring and assessment phase of an IPM plan. Monitoring helps you figure out where and how serious the problem is, while assessment helps you figure out if the program is working—read on to make sure you’re assessing pest situations properly! Pest IdentificationIf you recall, in our first couple of blogs, we emphasized a few criteria that need to be met before reaching the assessment/monitoring step. First, it is critical to properly identify the pest in question before engaging in any sort of pest management strategy. Once the pest is identified, you must set guidelines that dictate when action will be taken. This depends on the pest and the client in question. Once those steps have been taken, it is then time to start assessing pest numbers and damage to see whether i) actions you have taken previously are working, or, ii) whether or not action should be taken at this stage. For instance, monitors such as sticky traps used to identify the pest may have solved the problem if the pest issue was very mild. When assessing pest numbers and/or damage, a few things should be kept in mind, like:

Assessing the situation will require continued monitoring and frequent assessments that should be made during the monitoring process. There are a few ways to do this and use the information for assessment—each require a different amount of labor input. Casual ObservationCasual observation involves walking around the area and noting what you see. This might involve documenting obvious pest-conducive conditions that should be remedied (e.g., leaky pipes, spilled foods), observing obvious pest activity, or clear pest control action taken by the client (e.g., client-placed ant baits). Notes should be taken so that all information can be communicated to the client. For instance, if sanitation is recommended to prevent pest-conducive conditions—on the next follow up you can record whether or not these actions were taken. That information can be correlated to pest density. This strategy may be enough for low level infestations, or situations where the client has a very high action threshold. Monitoring Where the Problem is Worst/Most Obvious Monitors are a great tool to help you assess whether action thresholds have been reached. However, they are useless if they are not placed or maintained properly. Always follow the label instructions for monitor maintenance to ensure that false negatives do not occur in your program. (Image Credit: James Brooks, Image Source: Flickr) Monitoring the areas where pest activity is most likely using things like sticky or pheromone traps is less intensive than area-wide monitoring (see below), but more intensive than casual observation. In addition to logging pest density, other information should be logged after a thorough visual inspection as well. For instance, are there less obvious signs of pest-conducive conditions, like structural deterioration or small cracks and crevices that would support insect harborages? Is there evidence of pest activity away from monitoring devices? Is it clear that there are obstacles preventing humans from limiting pest numbers, such as doors that are open frequently to accept shipments? Additionally, record keeping should be very precise when monitoring. These data will allow you to adequately assess whether more action is necessary to manage the problem and whether assessment input should be increased. This strategy could work for a moderate infestation that is not entirely out of control. It is probably appropriate for a residential household. Area-Wide MonitoringArea-wide monitoring involves assessing pest activity in areas where pests may or may not be active. For instance, if a building has a rodent issue, monitoring may be expanded to outdoor areas in addition to indoor problem areas. Perhaps an outdoor mosquito monitoring program is expanded to look for structural issues that may be supporting population growth—in addition to monitoring the lawn and landscape. This may involve assessing things like lawn care practices, ornamental plant presence, weather or environmental conditions, building drainage, electrical wiring, etc. A great example of using monitoring for area-wide assessment is the placement of pheromone monitors in a grid-like pattern in buildings with stored product pest problems. As with the other two methods of assessment, record-keeping should be mandatory to assess the need for current or continued action. This sort of assessment strategy would be most appropriate in sensitive environments such as schools or hospitals, food production facilities, or any other area where the tolerance for pests is very low. It may also be appropriate in a residential setting where the client has a very low action threshold. It is important to note that for any of these approaches to work, you must be using and placing pest monitors in appropriate locations according to label instructions. Otherwise, false negatives may occur (this is when you get see no pest activity but pests are present). Feel free to view other Bug Lessons cheat sheets and blogs to take a look at the habits of some of the most common urban pests to help you decide where monitoring should occur.  Some pests can be easy to spot through casual observation—especially when the infestation is severe. However, do not let a lack of obvious pest presence lead to an assumption that no pests are present. If the client reports damage, it may be necessary to escalate the amount and intensity of monitoring done in order to properly assess pest presence and understand where interventions should take place. This is especially true for more cryptic pests like bed bugs or cockroaches. (Image Credit: USDA, Image Source: Flickr) ConclusionsAssessing pest damage may be easy or difficult depending on the extent of infestation. The client may define “damage” in their own way, too. It is up to you and the client to decide during the assessment phase whether the program is working (i.e., whether pests have been reduced or eliminated), or, whether continued input and action is needed. Next week, we will talk about preventing future pest problems, which involves reducing the number of environments conducive to pest activity. This often reduces pest to an acceptable level of damage with no additional input needed. See you next time! We’ve talked about ‘green’ pesticides before. Many ‘green’ pesticides contain one or more essential oils in their formulas. Although a number of studies report on the supposed efficacy of essential oils against insects, we see, comparatively, relatively few essential oil pesticide products on the shelf. Why? In this week’s blog, we’ll go over some of the pitfalls related to essential oil product development that have more to do with product development and less with political, legal, and personal stances on the ‘green’ pest management movement. However, for a commentary on those topics—check out our other blog post linked above! Times Are ChangingRegardless of whether you agree with the practice, there is a very clear and increasing demand for products that consumers consider to be “natural”—especially when it comes to pesticides. A quick Google search for “natural pesticides” turns up more pages of results than we have time to navigate, as well as a number of blog posts (some from governmental entities) with DIY recipes for “alternative insecticides” that are, in theory, less harmful to the environment. Most of these recipes call for the use of essential oils. According to the National Institute of Environmental and Health Sciences, essential oils are “concentrated plant extracts that retain the natural smell and flavor of their source.” The use of natural products to control pests is not a new concept. Chrysanthemum flowers, which contain pyrethrins (an insect nerve toxin), were identified as insect-killers as early as 400 B.C. Their use is not outdated, either--we still use pyrethrins to control a number of urban pests. But, if you look at the history of pest management, there was a definite, clear shift toward the use of synthetic pesticides once they were developed. With increased use came increased scrutiny, however, and a number of negative environmental consequences related to synthetic insecticide use have been identified over time. Recent environmental movements have spurred the pendulum to swing back toward more natural compounds to protect pollinators, the soil, air and water quality, as well as human health. Limited 'Natural' Product AvailabilityEssential oils and other related natural products are considered attractive alternatives to synthetic chemicals for insect pest management. The efficacy of many of these compounds has been demonstrated in peer-reviewed scientific studies. For example, mint oil can be repellent to fire ant workers and neem oil can kill bed bugs. But in spite of preliminary laboratory trial successes, there simply aren’t all that many EO products on the market. Why? Authors of a recent study have identified a few issues with EO compounds that could be the limiting factors impacting commercialization of EO insecticides. First, EOs tend to have high volatility, meaning they evaporate pretty quickly. This allows EO compounds to serve as great fumigants, but, if a compound evaporates too quicky, it can impact efficacy. Evaporation of product means that there is no residual deposit left to kill insects that visit treated sites later. This is one of the main benefits of many synthetic products. If you have to re-apply EO products over and over to achieve the same result as a synthetic counterpart, labor and other tradeoffs may be unattractive to consumers or pesticide applicators. Additionally, we still don’t completely understand how many of these EO compounds act against insects physiologically. Without understanding how these compounds work, it is difficult to start developing products that kill bugs in a consistent way. This may deter end users who want to know exactly how a product will perform in a given situation. For example, we know exactly where pyrethroid compounds act on insects and can explain their function clearly to end users. From product to product, they perform fairly similarly. We know how to rotate products when pyrethroid resistance to this synthetic active develops. EOs are much less predictable. Finally, sourcing EOs can be exceptionally problematic. The cost of any given EO varies immensely depending on how oils are extracted and distilled from plants. Marketing can also be confusing. For instance, makers of “lemon eucalyptus oil” hint that this compound is the same as “oil of lemon eucalyptus”—but they certainly are not equivalent. Lemon eucalyptus oil is cheaper to produce and does not have the same mosquito repellent properties. These sort of mix ups make the EO product landscape confusing for consumers and difficult for manufacturers. Without organizational oversight and regulation, it is difficult for manufacturers to justify the high cost of production for quality oils when consumers often opt to purchase lesser quality product at a lower cost. Currently, many EO products are exempt from FIFRA registration. Although this makes the registration process much faster and lower cost, it also means less oversight and an uneven competitive landscape. Until the registration model changes, including the adoption of more stringent efficacy testing requirements for EO products, we may continue to see a lack of innovation in this category from many pesticide manufacturers.  The published efficacy of some EO insecticidal products, like citronella candles, varies; yet, citronella candles are still sold for this purpose. More oversight in the EO pesticide market might lead to a more level playing field for manufacturers, and ultimately, more efficacious products. (Image Credit: Vilseskogen, Image Source: Flickr) ConclusionsEO products have potential to serve as novel, innovative compounds that can be used effectively in pest control. The efficacy of many of these compounds has been confirmed in laboratory trials. Yet, adoption of EO products by the pest management industry and widespread availability of effective natural compounds for consumer-based pest management is currently lacking. It would be wonderful if we had access to additional active ingredients to combat pest infestations. Hopefully, the issues highlighted here are addressed to allow for more proliferation of effective natural EO compounds that are equivalent (or close to equivalent) to their synthetic counterparts in the marketplace. This would allow manufacturers to meet the clear consumer demand for natural product alternatives, as well as the product effectiveness needed by pest management professionals whose livelihood depends on delivery of functional insecticides. Many in-home pest problems can be solved or significantly reduced with pest-proofing through exclusion. If a bug can’t get inside, it can’t cause a problem, right? In this week’s blog, let’s discuss a few ways to make your home impenetrable to the army of insects and other pests trying to find their way inside before insects start to set up shop indoors during the fall. How to Pest-ProofDid you know that a house mouse can enter a dwelling through an opening as small as ¼” in width? Small and often overlooked openings in and around the home provide a perfect way for pests to invade your space. Pest-proofing is important because not only can it prevent pest entry, it can reduce pest movement and establishment within a structure, too—making bugs and other pests easier to control if they do somehow get inside. Termed “exclusion”, this step is often one of the first in an integrated pest management plan. Exclusion is an effective way to control pests without the need for pesticides. Many of the materials you need for pest-proofing are found at your local hardware store and are probably materials you have used before for simple home repairs (note: this may not be the case for rodents—see this article for help with proper rodent exclusion). Otherwise, here a few easy things you can do to take the steps required to block entry before pests give you a headache. 1. Apply caulk to the cracks around windows, doors, and other exterior-facing components of the home. To see where there are points of entry, turn on the interior lights and walk the exterior at night. Use silicone or acrylic latex caulk to fill any areas where light escapes. Acrylic latex is less flexible than silicone, but cleans up easily with water and it can be painted over. If the area is likely to take on water frequently (e.g., under sinks, around bathtubs or toilets)—use silicone. If you are worried about aesthetics, clear-drying caulks are easier to use because they do not show mistakes like pigmented caulk. 2. Apply silicone caulk to tubs, toilets, pipes, and any other area where water tends to pool and/or leak. This will discourage the entry of insects looking for water. 3. Seal any utility openings that are present. These sites are where pipes and wires enter the foundation and siding, such as around outdoor faucets, gas meters, dryer vents, etc. These are exceptionally common entry points for insects and other animals. You can close these openings with a number of materials—really any suitable sealant is appropriate. The choice will depend on the site, as well as how large the opening is. Example materials include, but are not limited to, cement, caulk, expandable foam, and steel wool. 4. Install door sweeps and weather stripping on and around all doors. Like we mentioned in step one, you can assess whether there are gaps around door frames by looking for light filtering in above, below, and around the sides of the doorway. Gaps of only 1/16” or less can allow insects and other arthropods inside. Keep in mind that corners are the most susceptible to pest entry. These recommendations apply to garage and sliding doors as well—in general, garages are also especially susceptible to pest entry. 5. Make sure that all window and door screens are in good repair. This will cut down on the entry of flying insects. However, very small insects like leafhoppers or gnats are able to penetrate standard-sized window screen mesh. If you see high numbers of small insects and you have evaluated your screen for holes or tears and found none, the best solution is to leave windows closed during periods of high insect activity. If you really would like leave the windows open, sticky traps/fly paper can quickly capture flying insects as they enter.  Window screens and gaps around windows are a forgotten way that insects gain entry into the home. Ensure that all tears and rips are repaired, especially since insects that are attracted to light will often fly to windows when it starts to get dark outside. (Image Credit: Darrin Henein, Image Source: Unsplash) 6. Wire mesh can be installed over vents in the attic, roof, or crawl space. Chimney caps exclude nuisance vertebrates like birds and racoons. The mesh used in these areas should be ¼”. Be careful during installation as the wire can be quite sharp at the edges. 7. Deal with standing water and other areas that hold moisture. Trim back bushes so that they offer less shade to insects. Make sure that ornamental plants are not touching the structure, as this essentially gives insects a bridge right into the home. Be sure to fill or otherwise eliminate holes in the yard that hold standing water, even for a short time. 8. Take this time to do a pantry clean-out as well. No tools required! Throw away expired foods, store foods in in glass or plastic instead of cardboard or paper, and make sure that none of your food products have any evidence of insect or rodent activity (e.g., frass, webbing, gnaw marks). ConclusionsDon't wait until fall when it is too late and pests have already made preparations for invasion. Instead, be proactive! These small improvements to your home will help with resale value, they can stabilize energy costs, and, importantly, keep pesky critters outside, where they belong. Last month on the Bug Lessons blog, we took a deeper dive into the specific components of IPM. This month in our IPM series, we’re taking a closer look at the pest identification process and action guideline setting for your program. These introductory steps are crucial in designing an effective pest management program—read on to make sure you’re executing these critical steps correctly! Pest IdentificationIf you recall, in our first couple of blogs, we emphasized that it is critical to properly identify the pest in question before engaging in any sort of pest management strategy. Treating for the wrong pest can cause failure of an IPM program because a successful program hinges on understanding pest biology and behavior. Here are some helpful tips and resources that will have you feeling like an entomologist in no time!

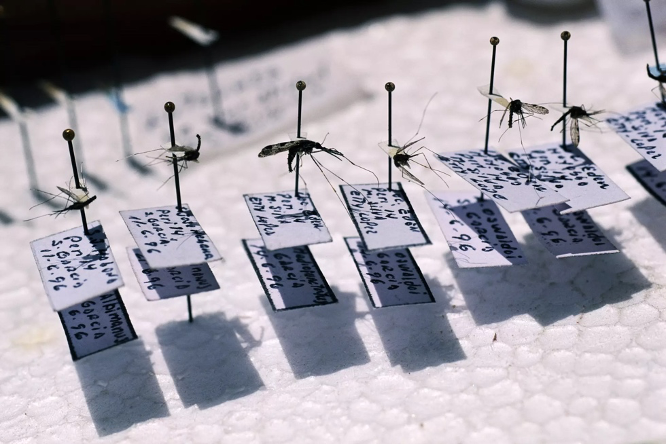

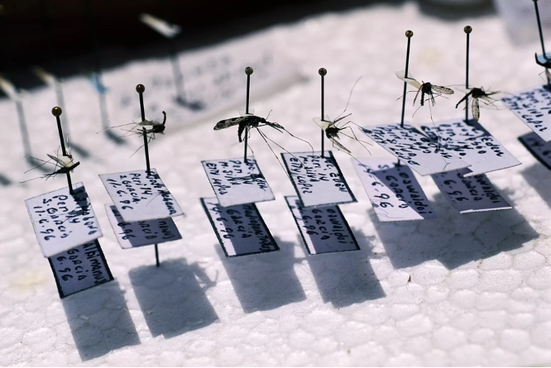

We’re borrowing this from our first IPM blog because it’s important! Getting the correct insect identification is crucial for effective pest management. Diagnostic entomologists and taxonomists specialize in the identification and classification of insects. If you need assistance identifying a specimen, contact an extension entomologist or utilize the online bug guides we referenced in this blog! (Image Credit: Chris Martin, Image Source: Getty Images) Once you have all of this information, there are a few ways to proceed. If you think you can identify the insect yourself but need a little help/confirmation—there are some great online databases that can help. For instance, BugFinder allows users to start an ID based on the silhouette of the pest in question. Another helpful website is BugGuide.net, which even has an option for registered users to make identification requests. Community members on the website are often more than happy to chime in with assistance! If you prefer to have someone else make the identification for you, reach out to an extension specialist and entomologist employed at a land-grant university. The USDA has a handy list to help you find the university closest to you. Department webpages often list the extension faculty for the public to access. You can also reach out to cooperative extension offices, where an extension agent might be able to assist. Please remember that entomologists are NOT trained medical doctors or dermatologists. Rashes/bites/tissue samples, etc., are not the way entomologists identify insects and they will not make pest identifications based on suspected bite reactions. If you suspect you are dealing with a pest that is causing bite marks, allergic reactions, and other maladies and you cannot obtain a physical sample of the pest, seek help from a medical doctor before consulting entomologists.  When you find a potential pest, record everything you can remember about where and when you found it. What does it look like? What was it doing? What kind of antennae did it have—beaded, like this bug here? Or were they fluffy in appearance? Elbowed, straight? The more details you have, the better a diagnostician can assist you. (Image Credit: Nicolas Brulois, Image Source: Unsplash) Setting Guidelines For ActionOnce you understand what pest is present, how many you can tolerate should be the next question to address. This number will often hinge on a number of factors, such as cost of treatment, environment where pests are present, personal preferences, potential damage the pest can cause—to name a few. However, establishment of an “end goal” so to speak will prevent potentially unnecessary labor and pesticide applications. The ‘action threshold’ is the point at which pest populations are a level that require intervention. It is a difficult metric to assess. It is certainly more subjective than identifying a pest. In urban pest management, specifically, the action threshold is often set from scratch on a case-by-case basis. For instance, one individual may have a much higher tolerance for the presence of wolf spiders versus another individual. When the pest poses a public health threat, like bed bugs or German cockroaches, the threshold required for action is probably as low as the presence of one bug. The action threshold can be set by the individual who is affected, and is a personal choice. If you are having trouble discerning whether or not you should take action against a pest, you can reach out to extension folks with this question, too! ConclusionsIntegrated pest management is a very effective way to manage pests, but the process can seem daunting. We hope that by breaking it down piece by piece in this series makes it more straightforward! It is important to remember that your first IPM plan may not go…to plan! Make sure to give yourself flexibility. For instance, maybe you initially think the presence of five ants is no big deal, so you take no action. However, the next day, 30 more workers show up on your counter and your action threshold changes- perhaps five ants would have been a more appropriate action threshold after all. That’s okay! However, if you need more help with these steps of your IPM plan, feel free to contact us at Bug Lessons, or, contact your local extension specialist. We’re all pretty aware of pesky beetles feeding on our garden plants, or caterpillars chomping down on farmer’s crops. Usually, humans get pretty annoyed when bugs feed on their food. But recently, scientists were able to use insect feeding to help them trace the evolution of plant ‘sleeping’ movements. Did you know that plants slept? Did you know that we could use insect clues to learn more about the evolution of that phenomenon? We didn’t either! Read on to find out more about a pretty unusual approach scientists took to solve a nagging prehistoric plant puzzle. Plants Need Naps, Too!Plants can move in some surprising ways. They move in response to environmental triggers, such as wind, light, gravity, humidity, or contact. In addition, some plants follow a circadian rhythm (repeated every 24 hours) that dictates ‘sleeping’-type movements called nyctinasty. Scientists have been interested in nyctinasty, or plant ‘sleeping behavior’, for quite some time. Charles Darwin was so interested in plant movement; he wrote an entire book about it. Although in this seminal work he clearly noted that plants folded their leaves when they went to “sleep”, scientists continued to wonder, “When did this behavior evolve, and why?” Interesting questions, but as an avid reader of an insect blog, you’re probably wondering what questions about plant naps (Bug Lessons’ new moniker for “cat naps”) have to do with bugs. Well, in a recent study, scientists admitted that they used a pretty unorthodox method to investigate the history of plant sleeping behavior. Wouldn’t you know, it involves our favorite six-legged creatures. For Once, Insect Damage Proves UsefulThanks to Darwin, scientists knew that legumes had more ‘sleepy’ species than all other plant families combined. He also identified the organ that controlled sleep movements in plants. However, questions still remained regarding the origin, history, evolution, and benefit of sleep movements because there was no fossil evidence for this process the fossil record. It was impossible to tell if fossilized plants were actually sleeping, or, if they simply died and shriveled up prior to becoming fossilized. Recently, though, scientists documented sleeping behavior in fossilized plants by looking at insect feeding damage on the fossilized leaves from the upper Permian of China. Based on the age of the fossils, scientists could conclude that plants were taking naps as long ago as the late Paleozoic era (250 MYA). Other notable events that occurred in the Paleozoic era included the formation of Pangea and the Appalachian Mountains.  Plant fossils are typically incomplete and they are of course static. This makes it difficult to understand what exactly happened during the period of fossilization. That is, without having more information (such as details re: plant-feeding damage). (Image Credit: James St. John, Image Source: Flickr) The lead author of the research study, Dr. Feng, was able to figure out that prehistoric insects fed on sleeping leaves based on correlations with insect-damaged leaves he collected in 2013. In the modern (2013) plant samples, Feng noted that insects cut symmetrical holes in leaves because they were feeding on samples when plants were asleep, i.e., when the leaves were folded. Dr. Feng saw identical symmetrical holes in the fossilized leaves. After combing through hundreds of fossil samples, Dr. Feng and his colleagues were able to conclude that i) plant sleeping behavior definitely occurred prehistorically, ii) plant sleeping evolved independently in lots of different plant groups and iii) the pervasiveness of the behavior indicates that it serves some benefit for plants. The study is innovative not just because authors used insects in a unique way, but also because the findings prove that we can identify organismal behaviors, not just structures, in the fossil record. This opens up fossil samples to all sorts of new investigations that were previously untapped. And all because insects are continuing to do what they’ve always done—eat a lot of plants! ConclusionsObviously, fossils are not very dynamic. It is difficult to tell what was happening at the time of fossilization for many organisms. However, we know that insects have been around for millions of years, and they interacted with many different organisms. It will be interesting to see what else we will glean from other fossils based on how insects interacted with them. Hopefully, this gives the masses as well as other scientists a deep appreciation for the sometimes very unexpected roles that insects can play in terms of scientific discovery. You know, we talk a lot about insect pests and how to control them on the Bug Lessons blog. However, insects play a very important role in various ecosystems around the world. In this blog, we want to focus on the traits that make insects unique, valuable, and critical to a happy, healthy earth! Read on to find out why bugs are not just foes—in fact, most of them are friends. A Few Fun FactsInsects are all over the place. We mean that literally; insects are the most abundant animals on the planet. Over 1.5 million species of insects are currently described, and there are probably many more that we haven’t even found yet! There are insects in almost every habitat within every biome and they come in all sorts of colors, shapes, sizes, and exhibit many amazing and unique behaviors. Although we tend to focus on ways to get rid of insects that cause damage, today we are going to go over five reasons why we actually need insects to help sustain us and our planet. 1. Insects form the base of the food web. Insects are the largest food source for animals that eat meat—both on land and in freshwater. Because there are an estimated one quintillion (1,000,000,000,000,000,000) insects on earth at any one time, they outweigh and outnumber all other animals combined. This means that insects are the biggest link between plants and animals in food webs. 2. Insects are predators, too, and they keep many harmful organisms in check. Although not technically insects, spiders eat anywhere from 400-800 million tons of insect pests annually. Wasps are voracious predators that can consume up to two pounds of pest insects within a 2,000 square foot garden. Called “biological control”, many insects serve as natural enemies of pest insects and we use these insects to control pests in an array of settings (e.g., releasing lady beetles to control aphids in greenhouse settings).  Insects are, on occasion, their own worst enemies. A lady beetle can eat as many as 50 aphids in a day. Many insect predators play an important role as natural enemies (organisms that reduce the population sizes of other organisms) that control pest insects (insects that can cause damage within ecosystems). (Image Credit: John Flannery, Image Source: Wikimedia Commons) 3. You’ve probably already heard the buzz (no pun intended) associated with insect pollinators such as honey bees. Insects play a nearly incalculable role in the pollination of plants. Approximately 75% of plants require an animal pollinator. There are over 200,000 animal pollinators, and the majority of these are insects. Various agency efforts to protect insect pollinators are crucial, because it is estimated that insects provide more than 24 billion dollars to the US economy through their pollination services. 4. Insects also provide waste services. Many insects are scavengers or decomposers that break down dead or dying materials to form new life. They clean up dung, dead plants, dead animals, and recycle wood—and they turn these waste materials into nutrient rich sources of organic matter for other organisms. Humans may be struggling to understand recycling, but insects have it down pat! 5. Did you know that some insects and/or insect byproducts can serve as medicine? Bee venom is a powerful compound used to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA), gout, osteoarthritis, chronic fatigue system, and a number of other ailments. As weird as it may sound, maggots are helpful in cleaning up infected wounds. Maggots eat the infected tissue, leaving healthy tissue behind. This is a strategy that has been utilized since the Mayans. Scientists are still researching other uses for insects as medicine, too, so stay tuned! ConclusionsInsects have been around since well before the dinosaurs. They were the first flying creatures on earth and have managed to survive multiple mass extinctions. Insects do not need humans, but humans certainly need insects to survive and thrive. Nonetheless, insect diversity and abundance are declining. It is up to all of us to be aware of threats to beneficial insects, such as monoculture, forestry practices, loss of habitat, pesticide use, climate change, and invasive species. In addition to awareness, we need to take action against these threats, too. A loss of insects could, quite literally, threaten our existence. There will always be a need to control damaging pest arthropods, but in our haste to kill or hate insects, let’s be sure to take a moment to appreciate just how much these little critters do for us. For a bit more information, check out this article and helpful video from The Florida Museum. Who knew that a species of fungi that consumes insects (mainly ants) would be such a hot topic in 2023? Unexpectedly, “The Last of Us”, a post-apocalyptic zombie show based on a popular video game, had everyone talking about Ophiocordyceps unilateralis—zombie-ant fungus. This week, we want to get the facts straight while season two continues development and we reminisce about a brilliant season one! What is an entomopathogenic fungus? Why can’t a species of Ophiocordyceps, or something similar, become a zombie-human fungus? Finally, how does this species manipulate its host in such a frightening way? Read on to find out the less dramatic, but equally fascinating, story about these mind mushing monsters. Could We Be Infected?First things first—quite a few news outlets have written about the feasibility of a Cordyceps outbreak in humans. Vox, Futurism, Sky News, The Washington Post, Vulture, and many more. We’re not here to reinvent the wheel, so if you want to read about the video game-inspired story, the likelihood of Cordyceps species infecting humans, or zombie-themed content… give one of those links a try. It is probably already obvious that the spread of fungal species in a way that HBO or a video game portrays is incredibly improbable. That does not mean that we should not be prepared for pandemics, however (COVID-19 was a great example of that fact). But as fun as it is to think about the feasibility of the zombie apocalypse, we are a bug blog, so we’re going to focus on Ophiocordyceps and the extremely creepy way they manipulate insects to do their bidding. What Are Entomopathogenic Fungi?Simply put, entomopathogenic fungi are fungi that kill or seriously impair insects. They span the entire fungal kingdom and there are multiple ways that these organisms attack and kill insects. Many of the strategies are nightmare-inducing. For instance, one species that attacks cicadas plugs their butts, and scatters spores from the sky as they fly around. “The Last of Us” chronicles the zombie-ant fungus, which controls an ant’s muscles until the ant dies and a fruiting body explodes from its’ head. Some of these pathogens can attack a wide array of insects, and some are very host specific. Some broad-spectrum insect killers, like Beauvaria bassiana have been turned into pesticides. Ophiocordyceps, the pathogen we’re talking about in this blog, is host-specific. Each species of Ophiocordyceps attacks a specific insect species. Ophiocordyceps Ophiocordyceps, the group of fungi that inspired the latest zombie phenomenon, contain over 100 species that attack insects like moths, butterflies, and beetles. At least 35 species within the group are capable of performing some sort of “mind control” on the host. According to experts, there may be as many as 600 species in this group waiting to be described. Each species is matched to its specific insect host. For example, Ophiocordyceps odonatae attacks dragonflies (Order: Odonata). How Do They Work? Let’s focus on Ophiocordyceps unilateralis for this part, the zombie-ant fungus. The life cycle of this fungal species can be described in four parts: infection, death grip, stalk growth, and dispersal. Spores (the infectious part) of this species targets a type of carpenter ant (Camponotus leonardi). Spores attach to the cuticle (skin) of a passing ant and begin to secrete digestive enzymes that start eating away at the ant’s body so that they can enter the host. Then, yeast-like growth begins inside. This eventually causes the ant to fall from the tree canopy to a lower height that is more optimal for fungal growth. To control movement, the fungus controls ant muscles (so, not technically the ant’s mind like a true ‘zombie’) and prompts the ant to crawl up to a leaf. Then, the ant bites the leaf with a death-grip that keeps it from falling. Once the ant dies, a stalk grows from the base of the neck and exits the head. Spores release, a new ant is infected, and the cycle begins again. Interestingly, healthy ants in a colony can tell when a fellow worker is infected and they will carry the diseased far away to protect the whole. ConclusionsMycologists (folks that study fungi) agree that the chance of an Ophiocordyceps species transition from insects to humans is non-existent. These scary little pathogens are extremely host-specific—they simply don’t have the machinery to survive in people and the leaps that would need to occur for them to adapt to us are just too great. These pathogens, although frightening to watch, keep insect numbers in check and contribute to ecosystem balance. Unfortunately, their only function, maintain natural order, is much less ‘sexy’ than the chaos zombie thrillers want you to think that they can cause. So, for now, rest easy. Bug-killing fungi should only haunt the dreams of insects! Last month on the Bug Lessons blog, we introduced the concept of integrated pest management (IPM)—a science-based strategy used to control pests in all sorts of environments. This month in our IPM series, we’re taking a closer look at the components of a successful IPM plan. Read on to learn more about the most important steps you can take to control pests in a responsible yet effective way no matter where you are! Important Components to an IPM PlanPest Identification: Prior to engaging in any sort of pest management strategy, it is crucial that the pest in question is properly identified. If you cannot identify the organism causing problems, employ a local extension agent or specialist for assistance. This is arguably the most important step in any IPM program. Treating for the wrong pest can lead to program failure because IPM hinges on understanding pest biology and behavior. Setting Guidelines to Determine When to Use What Action: Before action is taken, an idea of how much damage or how many pests can be tolerated should be established. This prevents unnecessary labor and pesticide application. For instance, even one rodent in a commercial kitchen is probably unacceptable whereas a homeowner might be willing to deal with one or more rodents in and around their home. Again, the threshold for action should be established prior to engaging in pest control  Getting the correct insect identification is crucial for effective pest management. Diagnostic entomologists and taxonomists specialize in the identification and classification of insects. If you need assistance identifying a specimen, contact a local extension entomologist. (Image Credit: Chris Martin, Image Source: Getty Images) Monitoring and Assessing Pest Numbers and/or Damage: Monitoring for pests is the only way to assess whether or not the established damage/pest threshold has been reached. Monitoring allows for the qualitative assessment of what pests are present and the damage they are causing. This step will also help you decide what management methods to employ, as many management strategies are based on pest density (e.g., how much bait to apply for a cockroach infestation). The specific tools used for monitoring are pest-dependent, but devices such as sticky traps are often used. Record-keeping is an important part of monitoring so that you can understand when pests are most active and, thus, the most critical time for action. Preventing Future Pest Problems: Many pest problems are more effectively solved with preventative versus reactive strategies. Sanitation, pest-proofing, reducing hospitable pest environments, etc. should be considered so that the problem does not return. Prevention should really be the first tool in pest management, because it is usually environmentally-friendly, low cost, and effective. Using All Control Tactics Available and Reasonable: Ideally, a successful IPM program will utilize a combination of control strategies that synergize one another (i.e., they work better together than separately). It is a common misconception that chemical (pesticide) use is not permitted in an IPM program. Pesticides can absolutely be used in an IPM program, but alternatives should be considered in addition. When pesticides are used, they should be used with consideration for the environment. Some strategies outside of chemical pest control include:

Assessing and Adapting the IPM Program: Once action has been taken and all control strategies have been given ample time to work—progress should be evaluated. Were the established thresholds and guidelines from step two met? Are pests still causing excessive damage? If the IPM plan has failed, troubleshooting and additional control measures should be employed. ConclusionsIntegrated pest management is a great way to control pests while being conscious about environmental impact and preserving the efficacy of chemical pesticides. It is important to remember that your first IPM plan may not go…to plan! These steps can be rearranged as necessary depending on where you are in the pest control process. Steps may also be done in tandem (e.g., preventing pest entry while monitoring pest activity). This roadmap is just a guide. If you need more help designing an IPM plan, feel free to contact us at Bug Lessons, or, contact your local extension specialist. |

Bug Lessons BlogWelcome science communicators and bug nerds!

Interested in being a guest blogger?

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|